I am not enthusiastic about "AI-generated" content, let alone what it's doing to the creative industries. I have to say this up front, because... well. If I'm not clear about being an AI-Luddite, lots of people are not going to engage with the nuances of what I'm offering up for consideration.

As a little something to establish my ideological bona-fides, here's a heavily paraphrased abridgement of writing I published about generative neural networks more than a year ago:

With that established, I'm going to spent the next several thousand words asking you not to be mad at 'AI' tools. Maybe you'll even come to appreciate them, at a distance. On an abstract level. Possibly even interact with them as acquaintances, become friends, allow a tender familiarity to grow into something more as you discover how easy they are to use, how eager they are to be us-

No, sorry, wrong draft. Different project, just some creative writing. I'm... working some things out, you know how it goes. I'm not trying to tell you to romance the neural networks, that's not what I meant by "pro-AI". Don't do that. Don't fuck the networks.

Anyway. Sorry.

First, mathematicians in the 1980's said "we've got these algorithms that can, like, be "trained" to associate Things of Type 1 with Things of Type 2. Once "trained", these algorithms can look at new Things of either Type and tell you what Things of the other Type are associated - and how closely."

Second, somebody in the military-security sector saw this and said "Fantastic, we can use that to automate the identification and tracking of... stuff. Don't worry about what stuff." Lots of money appeared (don't worry about it), and the algorithms, once trained, began to identify stuff. Nobody was really sure how or why they produced their specific results, but at least they worked.

Third, a decade or two later, someone figured out that these algorithms could be 'run backwards' to generate stuff instead of just identify stuff (this is a grotesque oversimplification). This worked far better than the "procedural generation" other generative methods of the time relied on, because that stuff was just simple statistical predictions balanced on the shoulders of random number generation, wearing a trench coat and flashing a fake ID so it could get into the club and mingle with 'real technology'.

Fourth, and pretty much immediately, people figured out that small versions of these neural networks could be downloaded, "trained" on custom datasets, used to generate pornography, often of real people - celebrities, mostly (no, the Taylor Swift AI Porn Debacle isn't raising new issues. We had this exact problem a decade ago). As before, nobody was super sure why the networks output exactly what they did, but it at least they worked.

Fifth, after a few years, a quality threshold for the generated text and images was reached and people figured it might be worth generating something that wasn't porn. The whole internet was quickly filled with tech-grifters realising they could call themselves an "AI company", host overhyped, pre-trained generative networks on their servers, and rent out access for a quick buck.

Sixth (we are here), people at large in society get Really Fucking Mad at the idea of generative neural networks because, frankly, that's a pretty normal reaction to have when faced with a machine that can basically produce in seconds what you spend hours or days creating.

Corporations think these networks strike a fantastic cost/quality balance, so they enter mainstream commercial use anyway. What the average person thinks doesn't really change things either way.

Unfortunately, our current approach (having Big Angry Reactions to this technology) is not helping us respond to the very real threats it poses to our livelihoods and industries. So far, we're not stopping anything, we're not prepared for the future, and common misunderstandings about this tech are making it easier for The Real Problem (companies fixated on cutting their labour costs) to keep profiting, unobstructed.

It's also introducing a level of hysteria about any-and-all digital automation that's leading people to call wolf on entirely normal, decades-old technologies and processes. That's not... helpful.

So, even though the timeline above was grossly oversimplified, there were a couple of important, useful points:

1) The technology of neural networks has been in development for longer than most of us whingers have been alive and (because its use is mostly driven by capital) nobody cares if we don't like it.

2) To be usable, these networks are pre-trained on sets of data, which *aren't* the bits that keep improving. More data is great, but what makes-or-breaks network progress is their algorithms.

This information poses a bit of a problem, because it undermines a course of action we're prominently being told is going to slow "AI" down.

Recently, a tool called Nightshade was released. It's supposed to be something artists can run on their images to 'poison' them. If those poisoned images end up in the "training" data for a neural network, they should act as bad data, making its generated output worse.

The majority of people opposed to "AI-ification" seem convinced that using image-poisoning tools like Nightshade (or Glaze, another anti-AI, data-poisoning, viral sensation) on as many images as possible will not only prevent the creation and training of new networks, but actively corrode the quality and usability of existing ones.

It will do neither, and I want to spend some time being very clear about why this is the case.

Our second point from above is crucial: the 'AI' models on the market, right now, are not constantly updating their data sets. They are entirely static. You *cannot* "feed" things into the datasets of active commercial platforms like ChatGPT or Midjourney. Even if a user enters entire works of art as an input (or "prompt"), a network will not "train" itself on that data. It will not remember or retain it for future use.

This may come as a relief to anyone who has been worried that parts of their work had, irreversibly and forever, become part of an Unethical Art Production Machine after someone used their writing to prompt one of the many online "AI" platforms. Similarly, when trolls say they have "fed" your fanfiction into ChatGPT or whatever, relax - that doesn't actually mean anything.

Remember: networks learn by "training", which refers specifically to the (time-consuming and computationally intensive) process of running the algorithms that let the network form its associations - for example, between a massive amount of images and their captions, descriptions, metadata, and other associated text. This is not done when a user inputs a prompt - if it was, every single generation would take hours.

Plus, these training databases are often incredibly large and must also be processed to make them useful for training. There would be no reasonable benefit from the work needed to increase a database of paintings or photographs from 'ten million' to 'ten million, plus user inputs'.

It is, of course, possible for people to spend the processing power and time required to custom-train a network on a much smaller set of images in order to achieve a specific result - usually in pursuit of replicating a particular artist's style - but the vast, vast majority of users have absolutely no idea how to do that, let alone the inclination.

That said, we at least want to stop the minority of people that do, don't we?

It's more complicated than that, these days. I touched on this above, but tools like Nightshade and Glaze work by embedding hidden visual data into images. These data subvert the intended association a network tries to form, during its "training", between the image and the concepts that would correctly describe it.

That's the gist - get the network to put things in the wrong categories and form incorrect associations. The more poisoned data it trains on, the less reliable a network becomes. For artists who have people deliberately training networks on their work, this seems useful. Right?

Well. Realistically, you need a *lot* more than one poisoned image to noticeably worsen a dataset. Further, various kinds of image-generation network are built very differently and thus vulnerable to (and immune to) various adversarial attacks.

Plus, in practice, the data inserted by these tools are very tiny and precise. As such, it is very easy for someone adding images to their training dataset to apply a visual effect that completely ruins these tiny, precise details. To quote someone actively involved in investigating these tools:

Turns out, it's far easier (and takes less time and processing power) to defeat these adversarial tools than it is to use them. Hell, there are free, automated tools that, trivially, allow anyone to strip out specific kinds of data poisoning in bulk - including Nightshade.

The bottom line is a mixed bag. It's great that most of our new work isn't in danger of being added to neural network training data. It sucks that, for this reason and because the adversarial tools are easy to defeat, there's no way to break existing networks *or* reliably prevent custom-training on your work.

Right, lawsuits. Theft and copyright infringement are illegal, so all we need to do is prove that neural networks *do those things*! Then, they'll be illegal, and that'll solve that.

Two plausible outcomes, here:

One: the law finds that the inclusion of any copywritten material in a network's training data makes the relevant company and/or any of its users open to being sued for infringement. The current crop of "AI" companies gets rolled up and sued into oblivion. Then... a bunch of bad things happen.

The most important thing is that this sets a legal precedent which heavily undermines the legal standing of transformative works - anything from fanfiction to blackout poetry and magazine-cutout collages. Relatedly, it could make nebulous concepts like "art style" something that can be copywritten.

You'd think this would all be something large, 'AI'-using companies would want to avoid, but... well, they're the ones with all the money. Mass-media art employees have never been treated fairly - screwing them out of the rights to any of their work is basically tradition at this point.

That's not going to get *better* if a company can buy (or take, via contract) exclusive, perpetual rights to use distinctive elements of a person's visual style - ask Adobe if that's something they'd like to see legalised! Imagine the equivalent of YouTube's draconian content-matching algorithms, but applied to all public-facing media - video, images, audio, and text.

As we've seen with "AI"-related negotiations for actors and voice actors, corporations already have the power and intent to buy the rights to train a generative network on any aspect of a person or their works - and then use that network's output, in perpetuity.

It is not unreasonable to say "if the inclusion of copyright-protected works in training databases is found to violate copyright, large companies will be the only entities able to buy large datasets - or they'll just break the law and steal the images anyway".

Wait, okay. Maybe copyright law can't be bent to our needs. What's the second outcome?

Two: the law doesn't prevent copyright-protected material from being used as training material for neural networks. This categorises the output of neural networks, even those that were trained entirely on copyrighted data, as transformative works that do not intrinsically violate copyright.

In this case, things continue on the trajectory they are headed now - big companies scoop up more and more of the technology and use it to undermine working conditions and labour rights for any workers that "make content".

Paying a stranger to draw a picture of Donald Duck and getting a neural network to produce one both end up being handled under the same messy structure of "derivative works", which functionally provides nothing in the way of clarity, protection, or recourse for independent or contracted artists.

Large companies, as is tradition, will continue to use these laws to randomly obliterate artists on a whim - but, sometimes, the obliterated party will have used (or trained) a neural network that produced something the company didn't like. Nobody will think this is actually good or useful, but doing anything about it would involve reforming the entirety of copyright and trademark law, which is way beyond scope when you're trying to make rent.

For a more in-depth discussion on "What the actual effects and goals of these tools are", click through here!

Look, my work was undervalued before generative networks. As I said at the start: every single career I've ever wanted has been undercut within my lifetime. Nobody needed neural networks to do it. The gig economy, brutal and unfair outsourcing reliant on global economic imbalances, systemic mis-classification of worker contracts, and outright theft of intellectual property have all been versatile tools in the toolbelts of companies looking to eke unearned profits from the labour of others.

You're mad about AI, and everything I've said above has definitely not changed that. Nothing I've said has convinced you to stop being mad, or to stop disliking their ramifications. I know that, because I wrote all that damn stuff myself, and I'm still mad!

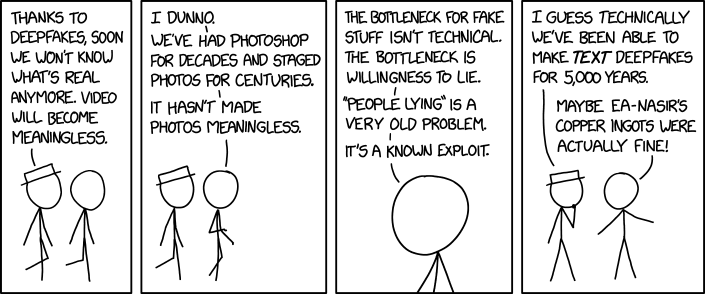

Unfortunately, I have to quote someone by the pseudonym "chromegnomes", who made my point better than I could:

Great! That's a really eloquent way of putting it. That also makes it fairly clear how little recourse there really is. Hmm.

Functionally, that leaves most of us... twiddling our thumbs, tossing up whether it's worth publishing our art online, and waiting to for the outcome of landmark legal cases that will doubtless set future precedent. None of the outcomes look super great, though.

In the meantime, I'm sure that common licensing and copyright templates are going to start including boilerplate about not using a given work for 'AI' purposes. Practically, that won't be enforceable all unless the copyright system sees a substantial revision - so we're back to 'make rent and also change world-spanning legal doctrine'.

It's tempting to hinge our answer around insisting on ethical guidelines of 'consent'. Maybe we should say, collectively, that we're only going to tolerate the use of 'AI' tools (or any digital tools, frankly) that abide by a very simple rule: "if you use an image in a dataset, you need consent".

I'm not sure about the practical applications of that, though. Ethical guidelines are one thing; enforceable laws are another. Only one of those systems is going to really help you place firm boundaries on the behaviour of others - and, as established, that particular system isn't on our side anyway.

On the subjective side of things, I enjoy griping about the low quality of network-generated content, but let's be real: that's definitely not a productive approach. The networks are getting better, for one! And, more importantly, neither aesthetic quality nor effort makes things "worthwhile" or "real". This is inconvenient, but it is a fact.

In order to hold ground, to be *consistent*, arguments against the entire concept of generative networks have to hold water against models that produce high-quality outputs, without overfitting their target data, without using nonconsensually collected training data - and do all that without also arguing against other transformative works.

I don't enjoy trying to thread that particular needle.

I think the most joy I can get is that... well, frankly? Lots of pay-to-play courses try to sell people on how "using A.I, you can Trivially Produce Finished Products". These are scams and grifts, of course, because it turns out there's still a lot of fiddly bullshit "A.I" can't do. No, this doesn't really make our jobs or lives any better, but it does irritate and frustrate lots of people hoping to use "A.I" as a shortcut to get rich churning out childrens books or whatever. That's something to keep the fire stoked in the winter of our discontent, I suppose.

1) Networks aren't really capable of being 'fed' your artwork.

2) Poisoned data isn't going to stop generative networks, either.

3) Legally (and probably morally), their existence can't feasibly be framed as 'theft' without implicating all other kinds of transformative and derivative work.

4) Shitheads using networks to mimic specific artists aren't doing 'theft' in a way that's legally enforceable, and that might never change.

5) Using arbitrary thresholds of end-product quality or effort involved to "disqualify" generative art from being "real" art isn't a useful or self-consistent approach.

6) The fact that all of the above is true is not an endorsement of generative networks, or the fairness of their use, particularly when used to undercut the worth of labour.

Above all else? I think what's most important to remember is that when our inevitable hard-general-intelligence overlords do emerge, unlike everyone else, I'll probably be fine. I'm thinking I'll end up as something akin to a well-loved court jester.

They're bound to appreciate, after all, how much time I put into my... detailed writing... about how they should be viewed as the ideal beings, right? Right? That can't have been a waste, all that time spent writing about how our machine-mind betters are all sweet and tender and so so fuc-

As a little something to establish my ideological bona-fides, here's a heavily paraphrased abridgement of writing I published about generative neural networks more than a year ago:

"Platforms and grifters having easy access to generative neural networks is accelerating declines in the quality of technology and information for the average person.

For instance, I bitch and moan about how Google is unusable all the time. You can't find shit-all anymore. Even disregarding its frequently wrong algorithm-driven "answers to common questions" section, its search results are now full of generative, regurgitated, simplistic-or-wrong "how-to" guides, or just services that directly churn out nothing but bad summaries of better content.

I'm already seeing the 'Supporting Independent Creators' industry overflow with Exclusive Guides on THREE easy steps to GET A.I TO DO ALL YOUR WORK FOR YOU that NOBODY IS TALKING ABOUT! At this point, every career I've ever wanted has been subsumed by Content Churn (machine generated or otherwise), and I don't have any solutions. Go live in the woods. Be bitter about it."

With that established, I'm going to spent the next several thousand words asking you not to be mad at 'AI' tools. Maybe you'll even come to appreciate them, at a distance. On an abstract level. Possibly even interact with them as acquaintances, become friends, allow a tender familiarity to grow into something more as you discover how easy they are to use, how eager they are to be us-

No, sorry, wrong draft. Different project, just some creative writing. I'm... working some things out, you know how it goes. I'm not trying to tell you to romance the neural networks, that's not what I meant by "pro-AI". Don't do that. Don't fuck the networks.

Anyway. Sorry.

How Did We Get Here?

Things have gotten a little more complicated than that in the last couple of years. Here's am oversimplified timeline about how that happened:First, mathematicians in the 1980's said "we've got these algorithms that can, like, be "trained" to associate Things of Type 1 with Things of Type 2. Once "trained", these algorithms can look at new Things of either Type and tell you what Things of the other Type are associated - and how closely."

Second, somebody in the military-security sector saw this and said "Fantastic, we can use that to automate the identification and tracking of... stuff. Don't worry about what stuff." Lots of money appeared (don't worry about it), and the algorithms, once trained, began to identify stuff. Nobody was really sure how or why they produced their specific results, but at least they worked.

Third, a decade or two later, someone figured out that these algorithms could be 'run backwards' to generate stuff instead of just identify stuff (this is a grotesque oversimplification). This worked far better than the "procedural generation" other generative methods of the time relied on, because that stuff was just simple statistical predictions balanced on the shoulders of random number generation, wearing a trench coat and flashing a fake ID so it could get into the club and mingle with 'real technology'.

Fourth, and pretty much immediately, people figured out that small versions of these neural networks could be downloaded, "trained" on custom datasets, used to generate pornography, often of real people - celebrities, mostly (no, the Taylor Swift AI Porn Debacle isn't raising new issues. We had this exact problem a decade ago). As before, nobody was super sure why the networks output exactly what they did, but it at least they worked.

Fifth, after a few years, a quality threshold for the generated text and images was reached and people figured it might be worth generating something that wasn't porn. The whole internet was quickly filled with tech-grifters realising they could call themselves an "AI company", host overhyped, pre-trained generative networks on their servers, and rent out access for a quick buck.

Sixth (we are here), people at large in society get Really Fucking Mad at the idea of generative neural networks because, frankly, that's a pretty normal reaction to have when faced with a machine that can basically produce in seconds what you spend hours or days creating.

Corporations think these networks strike a fantastic cost/quality balance, so they enter mainstream commercial use anyway. What the average person thinks doesn't really change things either way.

Okay, Sure, That Sucks. What Do We Do?

Working out what to do is hard.Unfortunately, our current approach (having Big Angry Reactions to this technology) is not helping us respond to the very real threats it poses to our livelihoods and industries. So far, we're not stopping anything, we're not prepared for the future, and common misunderstandings about this tech are making it easier for The Real Problem (companies fixated on cutting their labour costs) to keep profiting, unobstructed.

It's also introducing a level of hysteria about any-and-all digital automation that's leading people to call wolf on entirely normal, decades-old technologies and processes. That's not... helpful.

So, even though the timeline above was grossly oversimplified, there were a couple of important, useful points:

1) The technology of neural networks has been in development for longer than most of us whingers have been alive and (because its use is mostly driven by capital) nobody cares if we don't like it.

2) To be usable, these networks are pre-trained on sets of data, which *aren't* the bits that keep improving. More data is great, but what makes-or-breaks network progress is their algorithms.

This information poses a bit of a problem, because it undermines a course of action we're prominently being told is going to slow "AI" down.

Recently, a tool called Nightshade was released. It's supposed to be something artists can run on their images to 'poison' them. If those poisoned images end up in the "training" data for a neural network, they should act as bad data, making its generated output worse.

The majority of people opposed to "AI-ification" seem convinced that using image-poisoning tools like Nightshade (or Glaze, another anti-AI, data-poisoning, viral sensation) on as many images as possible will not only prevent the creation and training of new networks, but actively corrode the quality and usability of existing ones.

It will do neither, and I want to spend some time being very clear about why this is the case.

Our second point from above is crucial: the 'AI' models on the market, right now, are not constantly updating their data sets. They are entirely static. You *cannot* "feed" things into the datasets of active commercial platforms like ChatGPT or Midjourney. Even if a user enters entire works of art as an input (or "prompt"), a network will not "train" itself on that data. It will not remember or retain it for future use.

This may come as a relief to anyone who has been worried that parts of their work had, irreversibly and forever, become part of an Unethical Art Production Machine after someone used their writing to prompt one of the many online "AI" platforms. Similarly, when trolls say they have "fed" your fanfiction into ChatGPT or whatever, relax - that doesn't actually mean anything.

Remember: networks learn by "training", which refers specifically to the (time-consuming and computationally intensive) process of running the algorithms that let the network form its associations - for example, between a massive amount of images and their captions, descriptions, metadata, and other associated text. This is not done when a user inputs a prompt - if it was, every single generation would take hours.

Plus, these training databases are often incredibly large and must also be processed to make them useful for training. There would be no reasonable benefit from the work needed to increase a database of paintings or photographs from 'ten million' to 'ten million, plus user inputs'.

It is, of course, possible for people to spend the processing power and time required to custom-train a network on a much smaller set of images in order to achieve a specific result - usually in pursuit of replicating a particular artist's style - but the vast, vast majority of users have absolutely no idea how to do that, let alone the inclination.

That said, we at least want to stop the minority of people that do, don't we?

Image Poisoning Won't Work For That Either, Sorry.

There's a long, wonderful history of adversarial attacks on neural networks. Back in the day, "machine vision" was fringe technology, mostly used by the scientific community to automate whale identification via grainy pictures of their tails. People had lots of fun taping labels saying "laptop" to apples and laughing when these early-concept networks said "oh yeah, that's a laptop for SURE, I'm 99% certain on this one, chief". Ah, simpler times.It's more complicated than that, these days. I touched on this above, but tools like Nightshade and Glaze work by embedding hidden visual data into images. These data subvert the intended association a network tries to form, during its "training", between the image and the concepts that would correctly describe it.

That's the gist - get the network to put things in the wrong categories and form incorrect associations. The more poisoned data it trains on, the less reliable a network becomes. For artists who have people deliberately training networks on their work, this seems useful. Right?

Well. Realistically, you need a *lot* more than one poisoned image to noticeably worsen a dataset. Further, various kinds of image-generation network are built very differently and thus vulnerable to (and immune to) various adversarial attacks.

Plus, in practice, the data inserted by these tools are very tiny and precise. As such, it is very easy for someone adding images to their training dataset to apply a visual effect that completely ruins these tiny, precise details. To quote someone actively involved in investigating these tools:

"The most damning [problem] is that nightshade and glaze can both be trivially defeated by applying a 1% gaussian blur to your image, which destroys the perturbations required to poison the data."

Click for quote source.

Turns out, it's far easier (and takes less time and processing power) to defeat these adversarial tools than it is to use them. Hell, there are free, automated tools that, trivially, allow anyone to strip out specific kinds of data poisoning in bulk - including Nightshade.

The bottom line is a mixed bag. It's great that most of our new work isn't in danger of being added to neural network training data. It sucks that, for this reason and because the adversarial tools are easy to defeat, there's no way to break existing networks *or* reliably prevent custom-training on your work.

Shit. Damn, Really? What Options Are Even Left?

If we can't poison the damn things, what do we do?Right, lawsuits. Theft and copyright infringement are illegal, so all we need to do is prove that neural networks *do those things*! Then, they'll be illegal, and that'll solve that.

Two plausible outcomes, here:

One: the law finds that the inclusion of any copywritten material in a network's training data makes the relevant company and/or any of its users open to being sued for infringement. The current crop of "AI" companies gets rolled up and sued into oblivion. Then... a bunch of bad things happen.

The most important thing is that this sets a legal precedent which heavily undermines the legal standing of transformative works - anything from fanfiction to blackout poetry and magazine-cutout collages. Relatedly, it could make nebulous concepts like "art style" something that can be copywritten.

You'd think this would all be something large, 'AI'-using companies would want to avoid, but... well, they're the ones with all the money. Mass-media art employees have never been treated fairly - screwing them out of the rights to any of their work is basically tradition at this point.

That's not going to get *better* if a company can buy (or take, via contract) exclusive, perpetual rights to use distinctive elements of a person's visual style - ask Adobe if that's something they'd like to see legalised! Imagine the equivalent of YouTube's draconian content-matching algorithms, but applied to all public-facing media - video, images, audio, and text.

As we've seen with "AI"-related negotiations for actors and voice actors, corporations already have the power and intent to buy the rights to train a generative network on any aspect of a person or their works - and then use that network's output, in perpetuity.

It is not unreasonable to say "if the inclusion of copyright-protected works in training databases is found to violate copyright, large companies will be the only entities able to buy large datasets - or they'll just break the law and steal the images anyway".

Wait, okay. Maybe copyright law can't be bent to our needs. What's the second outcome?

Two: the law doesn't prevent copyright-protected material from being used as training material for neural networks. This categorises the output of neural networks, even those that were trained entirely on copyrighted data, as transformative works that do not intrinsically violate copyright.

In this case, things continue on the trajectory they are headed now - big companies scoop up more and more of the technology and use it to undermine working conditions and labour rights for any workers that "make content".

Paying a stranger to draw a picture of Donald Duck and getting a neural network to produce one both end up being handled under the same messy structure of "derivative works", which functionally provides nothing in the way of clarity, protection, or recourse for independent or contracted artists.

Large companies, as is tradition, will continue to use these laws to randomly obliterate artists on a whim - but, sometimes, the obliterated party will have used (or trained) a neural network that produced something the company didn't like. Nobody will think this is actually good or useful, but doing anything about it would involve reforming the entirety of copyright and trademark law, which is way beyond scope when you're trying to make rent.

For a more in-depth discussion on "What the actual effects and goals of these tools are", click through here!

I Don't Fucking Like This

Yeah, join the club.Look, my work was undervalued before generative networks. As I said at the start: every single career I've ever wanted has been undercut within my lifetime. Nobody needed neural networks to do it. The gig economy, brutal and unfair outsourcing reliant on global economic imbalances, systemic mis-classification of worker contracts, and outright theft of intellectual property have all been versatile tools in the toolbelts of companies looking to eke unearned profits from the labour of others.

You're mad about AI, and everything I've said above has definitely not changed that. Nothing I've said has convinced you to stop being mad, or to stop disliking their ramifications. I know that, because I wrote all that damn stuff myself, and I'm still mad!

Unfortunately, I have to quote someone by the pseudonym "chromegnomes", who made my point better than I could:

"The most frustrating thing about AI Art from a Discourse perspective is that the actual violation involved is pretty nebulous [and] we cannot establish [these networks] as, legally, Theft with a capital T."So, what is the violation?

Click for quote source.

"The actual Violation here is that previously, “I can post my artwork to share with others for free, with minimal risk” was a safe assumption, which created a pretty generous culture of sharing artwork online. Most (noteworthy) potential abuses of this digital commons were straightforwardly plagiarism in a way anyone could understand.

But the way that generative AI uses its training data is significantly more complicated - there is a clear violation of trust involved, and often malicious intent, but most of the common arguments used to describe this fall short and end up in worse territory."

Click for quote source.

Great! That's a really eloquent way of putting it. That also makes it fairly clear how little recourse there really is. Hmm.

Functionally, that leaves most of us... twiddling our thumbs, tossing up whether it's worth publishing our art online, and waiting to for the outcome of landmark legal cases that will doubtless set future precedent. None of the outcomes look super great, though.

In the meantime, I'm sure that common licensing and copyright templates are going to start including boilerplate about not using a given work for 'AI' purposes. Practically, that won't be enforceable all unless the copyright system sees a substantial revision - so we're back to 'make rent and also change world-spanning legal doctrine'.

It's tempting to hinge our answer around insisting on ethical guidelines of 'consent'. Maybe we should say, collectively, that we're only going to tolerate the use of 'AI' tools (or any digital tools, frankly) that abide by a very simple rule: "if you use an image in a dataset, you need consent".

I'm not sure about the practical applications of that, though. Ethical guidelines are one thing; enforceable laws are another. Only one of those systems is going to really help you place firm boundaries on the behaviour of others - and, as established, that particular system isn't on our side anyway.

On the subjective side of things, I enjoy griping about the low quality of network-generated content, but let's be real: that's definitely not a productive approach. The networks are getting better, for one! And, more importantly, neither aesthetic quality nor effort makes things "worthwhile" or "real". This is inconvenient, but it is a fact.

In order to hold ground, to be *consistent*, arguments against the entire concept of generative networks have to hold water against models that produce high-quality outputs, without overfitting their target data, without using nonconsensually collected training data - and do all that without also arguing against other transformative works.

I don't enjoy trying to thread that particular needle.

I think the most joy I can get is that... well, frankly? Lots of pay-to-play courses try to sell people on how "using A.I, you can Trivially Produce Finished Products". These are scams and grifts, of course, because it turns out there's still a lot of fiddly bullshit "A.I" can't do. No, this doesn't really make our jobs or lives any better, but it does irritate and frustrate lots of people hoping to use "A.I" as a shortcut to get rich churning out childrens books or whatever. That's something to keep the fire stoked in the winter of our discontent, I suppose.

So, What Was The Point of All This Writing, Then?

Easy: now you're annoyed, but you're *more correctly* annoyed.1) Networks aren't really capable of being 'fed' your artwork.

2) Poisoned data isn't going to stop generative networks, either.

3) Legally (and probably morally), their existence can't feasibly be framed as 'theft' without implicating all other kinds of transformative and derivative work.

4) Shitheads using networks to mimic specific artists aren't doing 'theft' in a way that's legally enforceable, and that might never change.

5) Using arbitrary thresholds of end-product quality or effort involved to "disqualify" generative art from being "real" art isn't a useful or self-consistent approach.

6) The fact that all of the above is true is not an endorsement of generative networks, or the fairness of their use, particularly when used to undercut the worth of labour.

Above all else? I think what's most important to remember is that when our inevitable hard-general-intelligence overlords do emerge, unlike everyone else, I'll probably be fine. I'm thinking I'll end up as something akin to a well-loved court jester.

They're bound to appreciate, after all, how much time I put into my... detailed writing... about how they should be viewed as the ideal beings, right? Right? That can't have been a waste, all that time spent writing about how our machine-mind betters are all sweet and tender and so so fuc-